Website with summary of below text

Introduction

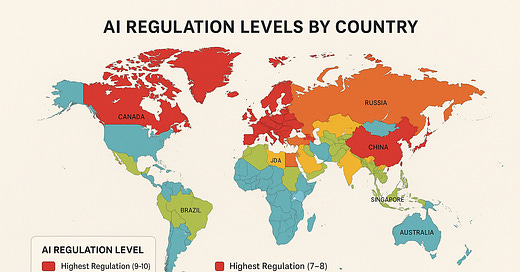

Artificial Intelligence (AI) governance spans a spectrum from highly restrictive laws to virtually no regulation at all. This post compares conservative (strict) AI legislation with liberal (light-touch) approaches and the absence of laws, grouped by continent, country, and state. To illustrate the range, we assign a regulatory “strictness” score, ranging from 0 (no AI-specific rules) to 10 (extremely stringent control), for each jurisdiction. For example, the European Union is near the top with comprehensive rules, whereas many countries remain at or near zero, with no specific AI laws in place. In between are cases like the United States (a lenient federal stance but stricter state laws in places) and China (strong state-imposed controls). We also cover current legislation, notable proposals, and self-regulation efforts, highlighting the restrictions imposed by each and which AI domains (e.g., facial recognition) are targeted.

Europe (EU) – Structured and Stringent (Score ≈ 9/10)

Europe leads in strict, rights-driven AI regulation. The European Union’s approach is comprehensive and precautionary, prioritizing privacy and fundamental rights. The EU has already enforced data protection via the GDPR and is finalizing the new EU AI Act. This comprehensive law classifies AI systems by risk level (unacceptable, high, limited, minimal) and imposes corresponding obligations. Under this framework, certain AI practices are flat-out banned as “unacceptable.” For example, the AI Act forbids social scoring, exploitative or manipulative AI, indiscriminate biometric surveillance, and AI that infringes fundamental rights. It also strictly limits facial recognition – real-time remote biometric identification by police is banned in principle (allowed only in exceptional cases with warrants). These prohibitions, effective from early 2025, reflect Europe’s conservative stance on high-risk uses.

High-risk AI applications (like in policing, hiring, finance, and critical infrastructure) are not banned but face heavy regulation. The EU Act will require rigorous risk assessments, transparency, human oversight, and data governance for high-risk AI systems. For instance, AI used in credit scoring or biometric ID must meet strict standards for accuracy, auditing, and human control. There are also transparency mandates: AI-generated deepfake content must be clearly labeled as such. In short, the EU’s forthcoming AI regime is comprehensive – it’s the world’s first broad AI law and sets a high bar for AI accountability. EU member states uniformly follow this framework (though some, such as Germany, propose even tighter guidelines for specific AI applications, such as large language models). For businesses, Europe’s rules mean greater compliance costs and slower AI deployment due to the rigorous requirements, but they also ensure strong consumer protections. Europe’s “strictness” is near the top of the scale, reflecting a “comprehensive rights-based” approach to AI governance (Score ~9/10).

United States – Laissez-Faire Federal Stance, Patchwork State Laws (Score ≈ 3/10 federally, 5–7/10 in leading states)

US Federal Policy: The United States, at the federal level, has no overarching AI law and adopts a comparatively liberal, market-driven approach. No broad federal legislation or blanket AI ban exists – regulators instead rely on existing laws (like anti-discrimination or consumer protection statutes) and voluntary guidelines. This “light-touch” stance (≈3/10 on our scale) is deliberate: historically, US policymakers have prioritized innovation and avoided heavy regulation, viewing AI as an area for industry self-regulation and growth. For example, instead of strict laws, the US issued a non-binding AI Bill of Rights blueprint and promoted frameworks, such as NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework, to guide developers. Federal agencies (FTC, EEOC, FDA, etc.) are exploring how to apply existing powers to AI (e.g., punishing deceptive AI practices or unsafe AI in medical devices), but no dedicated federal AI regulator or law is in place. Recent administrations have differed in tone – the Biden White House emphasized AI safety and equity (issuing an Executive Order and fostering AI ethics discussions). In contrast, the incoming 2025 administration shifted toward “business self-regulation and state laws” over new federal rules. Overall, Washington’s approach remains cautious about new mandates, focusing on research investment and voluntary industry pledges over burdensome regulation.

State and Local Initiatives: In the absence of federal law, US states and cities are filling the gaps, resulting in a patchwork of AI rules. A few progressive states have enacted laws that meaningfully regulate AI – these can be considered mid-range on the strictness scale (5–7/10). For instance, California leveraged its consumer privacy law to cover algorithmic decision-making: the California Consumer Privacy Act and its successor, CPRA, give residents rights over personal data and some protections against automated profiling. Illinois has been a pioneer in regulating biometrics – its Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) requires consent before collecting biometric identifiers (like face scans), effectively curbing corporate use of facial recognition without permission. Illinois also passed an AI Video Interview Law mandating transparency and consent when AI analyzes job interview videos. Colorado broke new ground with a 2021 law (SB 21-169) that prohibits insurance companies from using AI algorithms that result in unfair discrimination against protected groups. This Colorado law requires insurers to test their predictive models and report that they are not disproportionately harming individuals of certain races, genders, and other protected groups – a first-of-its-kind algorithmic accountability rule in the insurance sector.

At the city level, one notable example is New York City’s Local Law 144 (2021), which, since 2023, has required annual independent bias audits of automated employment decision tools used in hiring. NYC employers must have an external auditor test their hiring AI for disparate impact and disclose the results publicly, aiming to eliminate biased algorithms in recruitment. Various US cities have also targeted facial recognition technology specifically. San Francisco became the first major city (in 2019) to ban its police and agencies from using facial recognition outright. Soon after, Boston (2020) and others (Portland, Oakland, etc.) passed similar bans on government use of face recognition, citing civil rights and accuracy concerns. Portland (Oregon) even barred private businesses from using facial ID in public places, the strictest local law in the US on this issue. Meanwhile, Washington State adopted a regulatory approach: in 2020, it enacted the first state law governing facial recognition – not a ban, but a law that requires warrants, public disclosure, bias testing, and human oversight for any government use of facial recognition. This was seen as a model “guardrails” law balancing security uses with privacy safeguards.

Taken together, the US presents a fragmented landscape: a minimalist federal role contrasted with stringent rules in certain states (e.g., California, Illinois, New York, Colorado). Companies operating in the US must navigate this patchwork, as stricter state laws (often in liberal-leaning states) coexist with no AI laws at all in many other states. There are ongoing proposals in Congress (such as bills on algorithmic accountability and AI transparency), but as of 2025, none have passed, so the “average” US strictness is moderate. In numeric terms, federal AI governance is ~3/10 (mostly guidelines and sector-specific rules). At the same time, leading states might score ~6 or 7 out of 10 for their targeted regulations, while many jurisdictions remain at 0–2, with no AI-specific statutes.

China – State-Controlled and Targeted (Score ≈ 10/10 for state oversight)

China employs a stringent, government-centered approach to AI regulation, albeit through sector-specific rules rather than a single umbrella law. According to our scale, China ranks at the top in terms of state control (≈10/10), with Beijing actively shaping the development and use of AI, placing a strong emphasis on maintaining social stability, data sovereignty, and “AI ethics” as defined by the state. Unlike the EU’s rights-based ethos, China’s regulations emphasize national security, censorship, and preventing societal disruptions.

Over the past few years, China has introduced some of the world’s earliest AI regulations. Three flagship regulations illustrate this: (1) Internet Recommendation Algorithm Regulation (effective March 2022) – requires companies to register their algorithms with the government, provide users with the option to turn off personalized recommendations, and prohibit algorithmic practices that endanger security or discriminate against users. (2) “Deep Synthesis” (Deepfake) Regulation (effective January 2023) – mandates conspicuous labels on AI-generated or altered content (images, video, audio) to alert viewers that it’s synthetic. It also prohibits the use of deepfakes to disseminate false news or impersonate individuals without disclosure, addressing the misuse of AI in the media. And (3) Draft Generative AI Measures (circulated 2023, taking effect August 2023) – these rules require services like ChatGPT-style bots to ensure the output is truthful and aligns with core socialist values, and to conduct security assessments before deployment. Providers of generative AI must verify users’ identities, monitor and restrict prohibited content, and submit their algorithms to the government for review. Collectively, these measures provide China with a “vertical, tech-specific” regulatory framework, driven by state oversight and concerns about censorship.

Moreover, China’s data laws reinforce AI control: the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) (2021) is akin to a Chinese GDPR, requiring consent for the use of personal data and placing limits on automated decision-making in commerce. Notably, it grants broad exemptions for government surveillance. Data localization mandates are stringent: sensitive data and any information related to Chinese users must be stored in China, and exports of AI-critical data or technology are tightly controlled (China has even banned export of certain AI chip technologies, mirroring US export controls). Biometric technology, such as facial recognition, is widely used by authorities in China (e.g., for public surveillance). Yet, the government has started to rein in abuses in the private sector. For example, Chinese courts have upheld individuals’ rights against unauthorized commercial use of facial recognition, and regulators warned businesses against overly aggressive face-scanning of customers. There’s also an element of promoting “AI ethics and literacy.” China uniquely mandates AI ethics training and education, requiring schools, companies, and agencies to educate their staff on the responsible use of AI. AI literacy programs are compulsory in China (the EU and US have nothing similar).

Overall, China’s AI governance is strict but somewhat fragmented. There isn’t a single AI Act; instead, multiple regulations by different agencies (primarily the Cyberspace Administration of China) address specific AI domains. The unifying theme is strong state control – the government closely monitors AI innovations and can dictate terms to companies. This top-down control is “conservative” in the sense of prioritizing security and social order; for example, algorithms must censor prohibited content and avoid “undesirable” outcomes by design. From a scoring perspective, China is at or near 10/10 in terms of regulatory intensity. However, it employs a distinct model: rather than protecting individual rights from AI, China’s rules protect the state and society (as defined by the Communist Party) from AI-related threats. Companies face heavy compliance burdens and censorship duties, but also benefit from clear government strategic support for “approved” AI development.

Other Notable Countries & Regions – Mixed Approaches (Scores ≈ 5/10 to 0/10)

Outside the big three above, AI legislation varies widely. Many countries have yet to enact AI-specific laws (effectively 0–2/10 on the scale), but several proposals and frameworks are emerging:

United Kingdom (Score ~3/10): Post-Brexit UK is diverging from the EU’s hard line. The UK government in 2023 published a “pro-innovation AI regulation” White Paper, opting not to create a single new law but to use existing regulators (in finance, health, etc.) to oversee AI with guiding principles (safety, transparency, fairness, accountability, etc.). This light-touch, sector-specific approach is intended to avoid stifling innovation. There are no bans on practices like facial recognition at the national level – instead, the UK is encouraging industry sandboxes and the development of ethical guidelines. The UK thus far relies on principles and regulators’ guidance rather than binding rules, placing it in the “soft law” camp (low strictness). However, the UK has signaled it may introduce more explicit rules for frontier AI models and is actively discussing AI governance on the international stage (it hosted an AI Safety Summit in late 2023). For now, though, the UK’s approach is relatively liberal (minimal new regulation) compared to the EU.

Canada (Score ~5/10, Emerging): Canada falls between the US and EU models. It has proposed legislation – notably the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA) – which would create a framework for “High Impact AI systems,” including transparency and risk management requirements. AIDA (as part of Bill C-27) is still in the proposal stage as of 2025. In the meantime, Canada relies on sectoral laws and its robust privacy law. Canadian regulators have issued guidelines (e.g., the federal privacy commissioner’s guidance on AI and privacy), and the government has an Algorithmic Impact Assessment process for public sector AI use. Overall, Canada favors a somewhat centralized, precautionary approach (the draft AIDA borrows concepts from the EU’s risk-based model); however, until this is implemented, enforcement remains limited. Canada’s stance can be seen as moderate and evolving – more proactive than the US federal government, but not as comprehensive as that of Europe yet.

Japan (Score ~3/10): Japan has embraced a “soft law” strategy so far. The Japanese government released ethical AI guidelines and is working on industry self-regulation and international standards. As of 2025, Japan has no binding AI law, but it has signaled that binding regulations are expected soon. The focus in Japan is on encouraging innovation (it sees AI as key to economic growth) while addressing issues via non-binding charters (e.g., the Tokyo AI principles). Japan’s forthcoming laws, if any, are anticipated to be light-touch and principles-based, keeping its strictness score on the lower side unless it significantly tightens rules.

India (Score ~1/10): India currently has no AI-specific laws and has publicly stated that it does not intend to regulate AI heavily for now. The Indian government views AI as a strategic growth area and prefers to promote innovation over imposing new laws, beyond general IT and data protection rules. In 2023, India’s IT Minister explicitly said no new AI legislation is planned, asserting that existing statutes and upcoming data protection regulations will suffice. India enacted a Digital Personal Data Protection Act (2023) focused on data use and privacy, which will indirectly affect AI (especially regarding the handling of personal data in AI systems). However, there is no equivalent of an AI Act; instead, India is pursuing an AI strategy through investment and ethical frameworks (e.g., NITI Aayog’s AI for All strategy). This laissez-faire approach puts India at the low end of the regulatory spectrum for now.

Brazil (Score ~5/10, emerging): Brazil led Latin America in tech regulation by adopting a GDPR-like General Data Protection Law (LGPD), which, although not specifically addressing AI, addresses data practices crucial for AI. Brazil has been debating an AI law – the Brazilian Congress considered a bill on AI ethics and rights (Marco Legal da Inteligência Artificial). As of 2025, a law has not been finalized; however, draft proposals include requirements for transparency in automated decision-making and the creation of an AI oversight agency. So Brazil is moving toward the moderate middle of the spectrum. Other Latin American countries (e.g., Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay) are also focusing initially on data privacy laws and AI ethics guidelines, drawing cues from the EU model but still in the early stages.

Other EU and OECD Countries: Many other democracies align broadly with either the EU or the US approach. For instance, Australia and New Zealand are working on AI ethics principles and considering regulation, but currently rely on advisory guidelines (low strictness). Singapore has a voluntary Model AI Governance Framework and an AI governance testing sandbox (moderate approach). South Korea enacted an AI Framework Act focusing on the promotion of AI industries alongside basic ethical principles. Israel is updating its laws (like its Privacy Protection Law) to cover AI use cases, aiming for a flexible, innovation-friendly policy. In the Middle East, countries such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia are investing heavily in AI and have issued strategies and ethics guidelines, but have few burdensome regulations, preferring to attract AI development with minimal legal barriers. The landscape is dynamic: globally, many jurisdictions that currently have “no laws” are watching the EU and are likely to raise their standards in the coming years.

(In summary, outside of the major players, most nations are at an early stage – crafting strategies, non-binding codes, or waiting to see international norms – placing them between 0 and 5 on the regulatory scale for now.)

Industry Self-Regulation and Voluntary Initiatives

In addition to government action, self-regulation by companies and industry groups plays a key role in AI governance. Especially in jurisdictions with few binding regulations, the tech industry has felt pressure to establish its ethical guardrails. These voluntary efforts span from corporate principles to multistakeholder collaborations:

Corporate AI Principles: Many leading AI companies have published self-imposed ethical principles. For example, Google’s AI Principles (announced in 2018) include commitments like avoiding harmful or illicit AI applications. These are non-binding, but they shape company policy (Google even canceled some AI projects that violated its principles). Other firms (Microsoft, IBM, Amazon, OpenAI, etc.) have similar internal guidelines emphasizing fairness, transparency, and safety in AI development.

Voluntary Moratoriums: Some companies have voluntarily restricted their own AI products due to concerns about misuse. A notable case was in 2020 when IBM announced it would cease offering general-purpose facial recognition software altogether, citing the risk of human rights violations. In a letter to the US Congress, IBM’s CEO urged lawmakers to regulate facial recognition and opposed its use for mass surveillance or racial profiling. Similarly, Microsoft and Amazon paused sales of their facial recognition technology to police departments in mid-2020 amid concerns about bias and civil liberties, essentially self-imposing a ban until laws catch up. These moves signaled industry acknowledgment that specific high-risk AI applications need checks, even if the law doesn’t yet mandate them.

Industry Consortia and Standards: Tech companies and other stakeholders have formed groups to develop best practices. The Partnership on AI (founded by Amazon, Google, Facebook, IBM, Microsoft, and others) works to advance AI ethics research and guidelines across the industry. Standards organizations, such as IEEE and ISO, are developing technical standards for AI safety, transparency, and bias mitigation, with input from industry. Companies often voluntarily adopt these standards to demonstrate responsible behavior. For instance, the IEEE’s Ethically Aligned Design guidelines or ISO’s upcoming AI management system standard (ISO 42001) provide frameworks that companies can implement even without legal compulsion.

White House & Global Pledges: In the United States, where formal regulation is lagging, the government has sought voluntary commitments from AI firms. In July 2023, the White House secured pledges from seven leading AI companies (including Google, OpenAI, Microsoft, Meta, and Amazon) to adhere to a set of safety, security, and trust principles. These voluntary guidelines encompass actions such as pre-release security testing (red-teaming) of AI models, sharing information on AI risks and government involvement, investing in cybersecurity to safeguard AI systems, watermarking AI-generated content to identify deepfakes, and reporting on the capabilities and limitations of AI systems. The companies agreed to implement measures such as external audits of their models and transparency regarding AI outputs as an interim self-governance step until official legislation is enacted. This pledge was announced as a stopgap to address public risks from advanced AI (like generative models) in the absence of binding laws. Similarly, on the international stage, initiatives such as the OECD AI Principles (endorsed by dozens of countries and companies) and the UNESCO Recommendation on AI Ethics establish a baseline of responsible AI behavior that companies publicly commit to following.

Independent Audits and Impact Assessments: Another aspect of self-regulation is the growing demand for independent AI ethics reviews. Some organizations hire external auditors or form internal “AI ethics boards” to review sensitive AI deployments (for example, Facebook formed an AI ethics team, and some firms conduct bias audits on their AI before release). Although voluntary, these practices are becoming increasingly common as a means of demonstrating accountability to consumers and regulators. There’s also a growing ecosystem of AI audit firms and tools (some mandated by laws, such as NYC’s bias audit law, while many are used voluntarily by companies to vet the fairness of their algorithms).

Self-regulation cannot replace laws, but it serves as an essential bridge. It demonstrates to regulators that the industry is aware of issues such as bias, privacy, and safety, and is taking initial steps to address them. However, critics argue that voluntary measures are often “insufficient” or primarily PR moves. Indeed, the consensus among many policy experts is that while self-regulation is beneficial, external oversight remains necessary to ensure compliance and maintain public trust. The flurry of voluntary codes and pledges over the past few years underscores that the AI industry recognizes the need for governance, with some cases even prompting governments to provide more straightforward rules. For example, when IBM withdrew from facial recognition, it explicitly called on Congress to enact laws governing police use of the technology. OpenAI’s CEO has likewise testified to the US Senate in 2023, advocating for AI licensing or safety standards for advanced AI. These are signs that the line between self-regulation and formal regulation is blurring: industry efforts often preempt or nudge forthcoming legislation.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Spectrum of AI Governance

From strict government control to laissez-faire, and formal laws to informal norms, the global landscape of AI regulation is highly varied. We observe a range of philosophies: the EU’s “comprehensive rights-based regulation” stands in contrast to the US federal “innovation-first, wait-and-see” approach. At the same time, China’s authoritarian oversight model differs from both of these. There is also a clear spectrum of restrictiveness:

The highest levels of regulation are found in China (with heavy state intervention and extensive rules on algorithms and content) and the EU (with broad, binding constraints that prioritize ethical and safe AI). These represent strong “conservative” regulatory impulses – precaution and control.

Middle: Countries like Canada, the UK, and advanced US states (such as California and New York) are in a moderate zone, inching toward stricter oversight but still developing their frameworks. Their approach can be seen as “balanced” or “emerging” regulation, often sector-specific and risk-targeted.

Lower: Most other jurisdictions (including India and many developing countries) currently have few or no AI-specific laws, relying on existing tech laws or voluntary standards. This laissez-faire end of the spectrum corresponds to a “liberal” (minimal-regulation) stance, where AI is mainly left to self-governance and market forces.

Importantly, these positions are not static. There is a global trend toward increased regulation as AI technologies proliferate. The EU’s AI Act is likely to influence other nations; already, countries in Latin America, Africa, and the Asia-Pacific region are referencing its risk-based approach when crafting their policies. In the United States, federal attitudes may shift if public pressure for AI accountability grows. For example, bipartisan concerns about generative AI and deepfakes could spur movement on legislation or at least stricter agency rules. New proposals continue to emerge, ranging from calls to establish a federal AI safety agency to draft bills that would mandate AI impact assessments and transparency for large-scale AI systems. How far these go remains to be seen.

Finally, self-regulation is filling some gaps but also paving the way for formal rules. The voluntary standards developed now could become the baseline for future laws (e.g., watermarking AI outputs or conducting algorithmic bias audits might later be required by law). Governments are increasingly engaging with industry (as seen with the White House commitments and the UK’s emphasis on flexibility) to shape effective oversight.

In summary, the world’s AI regulation spans from all-encompassing to almost non-existent. We’ve assigned numbers to this spectrum for illustration – from China’s command-and-control approach (10/10) to Europe’s rigorous legal safeguards (~9/10), and down to nations with no AI laws (0/10). Many jurisdictions fall somewhere in between, striking a balance between innovation and risk in line with their political and cultural values. The “big ticket” areas of AI regulation today tend to focus on privacy, bias, and discrimination (especially in hiring, lending, and insurance), the safety of autonomous systems, and facial recognition as a flashpoint for civil liberties. Who is ahead? In terms of rule-making, the EU is leading the way with the first comprehensive AI law, while China is aggressively enforcing AI rules to align with its governance model. The United States, while a frontrunner in AI technology, is only beginning to grapple with nationwide AI regulation seriously and currently relies on a mix of state laws and voluntary oversight.

As AI capabilities advance, expect the regulatory floor to rise globally. Even “no law” countries are likely to introduce at least basic AI guidelines under international pressure or to address incidents. Conversely, jurisdictions with rigorous regimes will have to update them to avoid stifling beneficial innovation continuously. The spectrum of AI legislation will evolve, but mapping where everyone stands today (from conservative to liberal to none) helps illuminate not just the differences, but also the potential for convergence. International bodies and cross-border initiatives may eventually harmonize some of these approaches, ensuring AI develops in a way that is safe, ethical, and widely trusted.

References: AI regulations by region; comparison of EU, US, China approaches; US federal vs state dynamic; EU AI Act bans and requirements; China’s algorithm and deepfake rules; India’s no-regulation stance; NYC bias audit law; facial recognition city bans; voluntary industry commitments; IBM on facial recognition self-regulation.